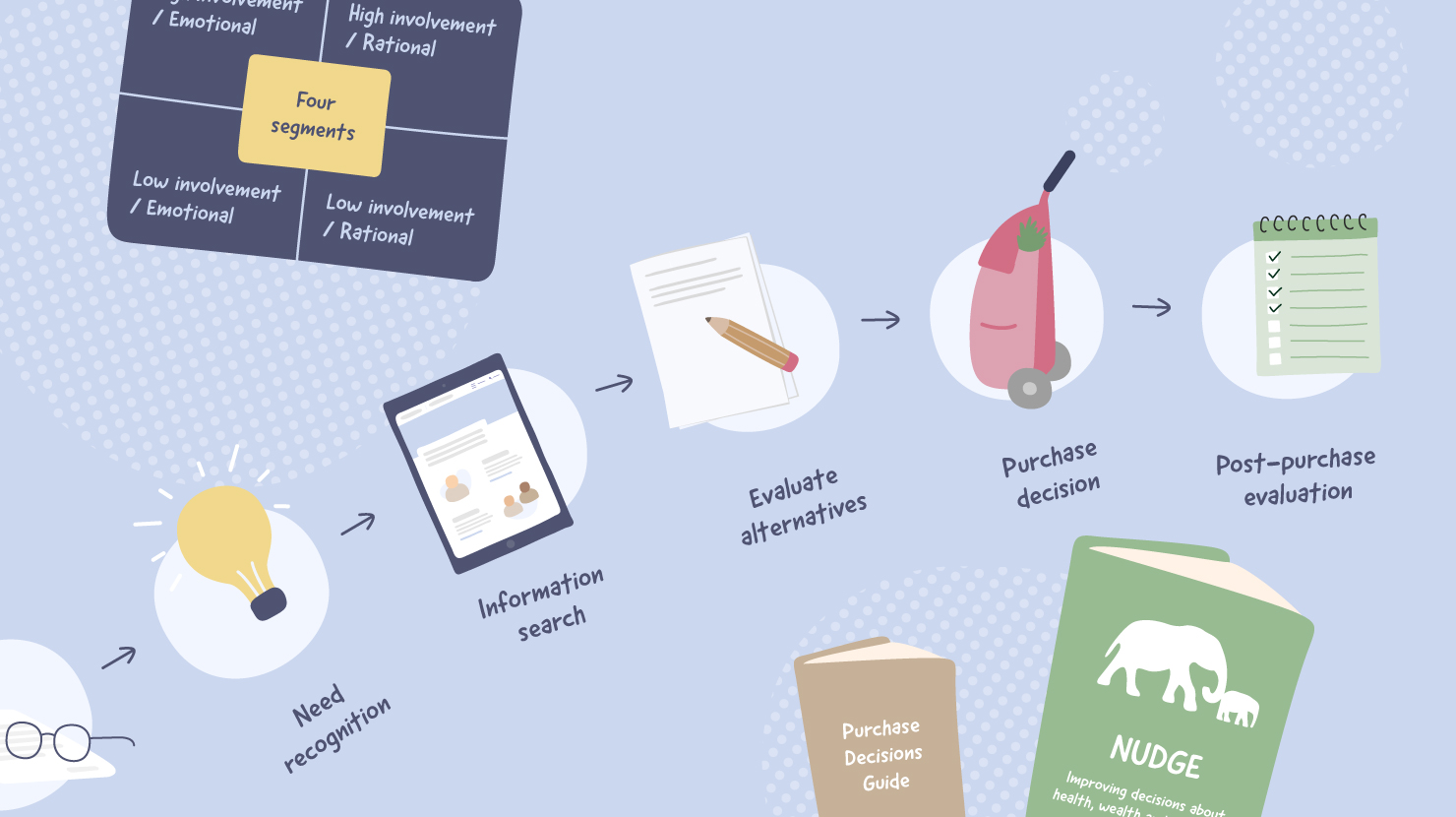

For decades, economists, psychologists, and academics have come up with definitions, theories, and hypotheses about how human beings make decisions. Marketers have studied and experimented with nudge theory, the five steps of decision-making, consumer involvement theory, and more—all with the aim of finding out what makes people do the things they do.

Every new theory, new study, and fresh insight into the whats and whys of consumer behaviour is valuable. But it’s important to remember that behind every action and every behaviour, there are people. Not consumers. Not customers. Not users. Just regular people with needs and wants—sometimes small, sometimes big, and always complex.

Aspirational versus unavoidable

If we look at traditional high involvement purchase decisions, they generally involve a big—or big enough—positive life change of some sort. For example, buying a car, or a house, or even an engagement ring.

On one hand, these decisions involve a change of status in some way. On the other hand, many of them also entail emotional consequences if the wrong decision is made. Most people don’t make these decisions lightly; they make them after extensive research, consultation, comparison, and evaluation.

So, if something positive and aspirational involves so much planning and thinking and research, what about the decisions that people often have to but don’t really want to make at some point in their lives?

How do we as marketers, CX strategists, experience designers and the like make a “high involvement, low motivation” decision-making process more encouraging and less daunting?

Lessons learned from aged care

We gained some valuable insights through our work on the My Aged Care website: the starting point to access Australian Government-funded aged care services.

At its heart, the project we undertook for My Aged Care was about journeys—personal and organisational. We’ll talk about the personal journey—that of older Australians and their support networks, the challenges of adjusting to ageing, and the emotions and needs that come with it.

Our objective was to create an experience that would provide information, reassurance, and guidance to this audience to help them get all the support they would need to live better quality, longer lives.

Our own journey was filled with realisations, some of which were anticipated and some, very surprising. Through a continuous process of investigation, observation, and collaboration, we were able to distill our learnings down to some core principles that can be applied to different journeys:

1. Start by recognising the human concerns

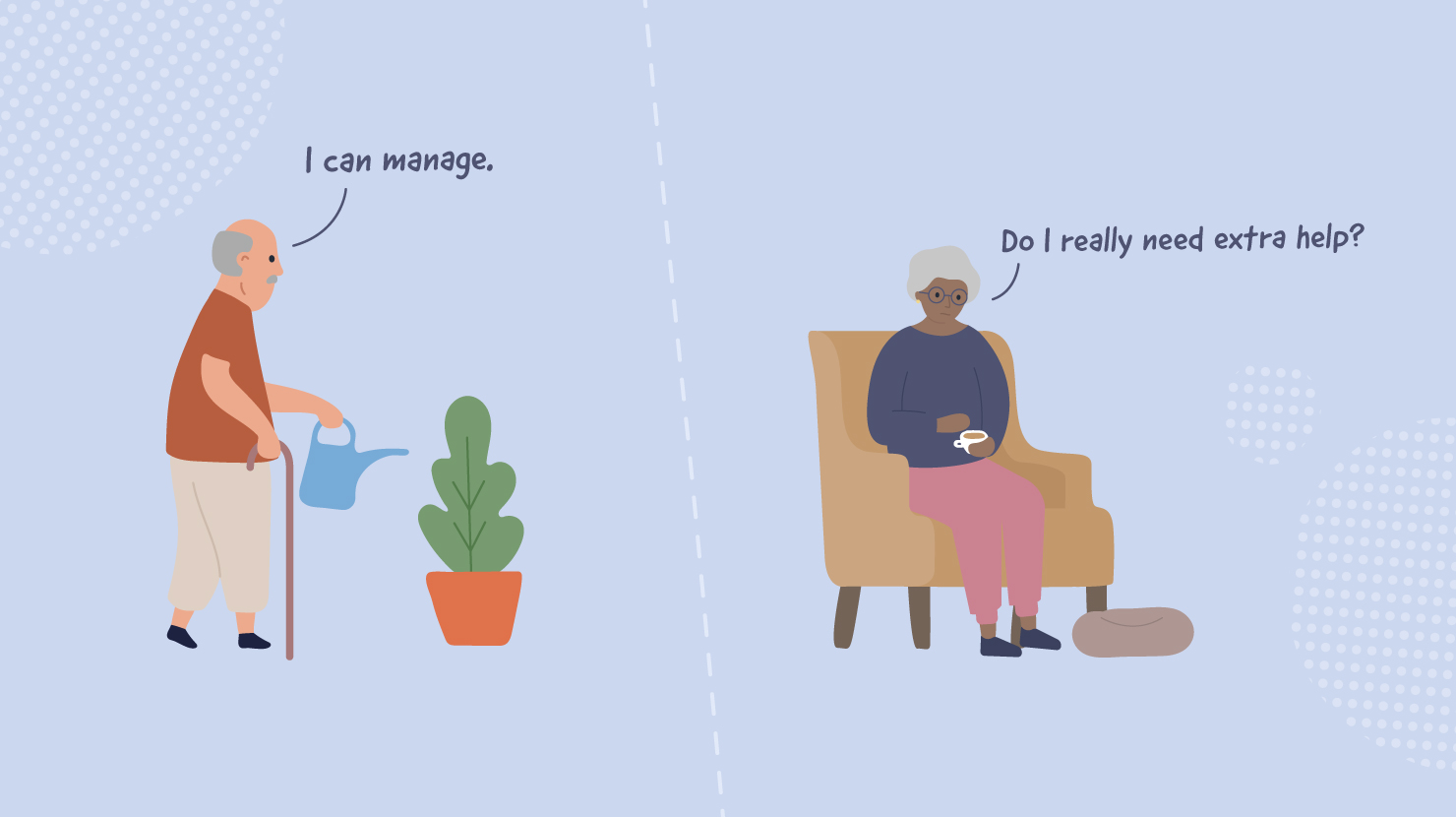

Let’s look at Beth*, a 70-year-old woman who lives alone. She’s self-sufficient, independent, and generally healthy. But lately, she’s been feeling like she could use a bit of help with tasks like gardening and house cleaning, which can be pretty strenuous work.Beth knows she would benefit from some help, but she feels reluctant to take any action just yet. Questions and thoughts start to swirl around in her head, like:

- Do I really need extra help? I’m healthy, and the exercise does me good.

- Maybe I can ask the kids to help out? No, if I tell them, they’ll worry about me, or try to convince me to move in with them.

- Can I get someone to help out at home a few times a week? Is that a thing?

- If not, what are my options? Moving in with one of the kids, or into a nursing home? If those are my only options, maybe it’s best to not say anything. I’m not that helpless yet. I can manage.

None of these scenarios are aspirational or appealing.

Let’s face it. Most of us don’t like asking for help. It makes us feel vulnerable, or weak. And most of us are afraid of getting old. The two go hand in hand, more often than not. Getting old plus needing help inevitably means losing independence.

Takeaway: Getting to the heart of the issue is a crucial first step in helping people overcome barriers to decision-making.

* Fictitious character, example based on common real-life experiences.

2. Make it relatable with authentic stories

Once we understand what the core issue is, we can figure out how to make it less scary and more manageable. We can turn the perceived issue on its head by normalising it and making it relatable.

We’ve established that emotions like fear and pride stop people from asking for help. So why not appeal to positive emotions, like empathy? One way to do that is through authentic stories told by real people in situations similar to Beth’s—stories that reassure people that they’re not alone, that everyone gets older, that it's normal to need help no matter what age, and that getting help won’t turn their lives upside down.

In telling these stories, it’s important to make sure they’re inclusive. Someone from a culturally and linguistically diverse background might have very different concerns from Beth’s. Seeing themselves in one of the stories could be a catalyst in their decision-making process. This can be applied to people from different cultural backgrounds, religions, socioeconomic status, and so on.

Takeaway: Storytelling is a powerful tool. Real-life stories of regular people add a personal, human element that no other form of content can.

3. Involve real people in the design process

Human beings have many biases. We tend to make assumptions about how common our beliefs, opinions, interests, and preferences are to those of others around us. This is a cognitive bias known as the false-consensus effect, and it can be quite limiting and counterproductive.

That’s where the popular UX adage “You are not the user” comes in handy. It may seem like a no-brainer, but keeping the false-consensus effect in mind, it’s worth reminding ourselves of this every now and then. It helps keep us grounded.

It’s unfortunate how often user testing is overlooked, or not done the proper way, for one (or some) of the usual reasons: lack of budget, lack of time, not enough motivation to get that invested, ignorance about how to go about doing it, lack of understanding of its long-term value, poor planning… The list goes on. However, if you really care about building something that people are going to use, and love using, no excuse is good enough not to do it.

Putting yourselves in your customers’ shoes is a good exercise, but nothing can be more insightful than putting your product (or experience) right in front of them, early in the game, watching how they interact with it, what they enjoy, what they struggle with, and taking lots of notes along the way.

Takeaway: Once you understand what your customers are looking for and what’s missing, you can use that knowledge to adapt and improve the experience, as often as needed and possible. User testing, when done well, is irreplaceable.

Observe, adapt, evolve

These principles aren’t hard to put into practice. The biggest hurdle is often related to changing your mindset (or someone else’s) to recognise their value. Once you’ve done that, the only thing you need to focus on is continuous improvement. Observe and listen to what the users are saying, adapt your approach as you go, and do whatever you can to ensure that you’re evolving and building a journey that any of your users would be ready to make.

When we take a human-centred approach rather than a “customer-centred” one, many other pieces often fall into place naturally, and the outcomes can be eye-opening.